Letter from Caracas

Slumlord

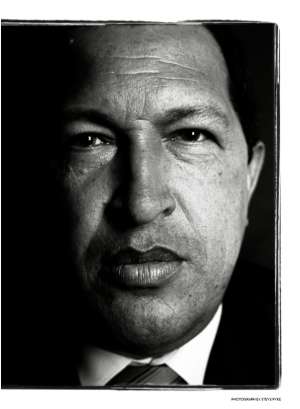

What has Hugo Chávez wrought in Venezuela?

by Jon Lee Anderson January 28, 2013

Subscribers can read the full version of this story by logging into our digital archive. You can also subscribe now or find out about other ways to read The New Yorker digitally.

ABSTRACT:LETTER FROM CARACAS about the

Tower of David, which is the world’s tallest slum, and the man who runs

it, Alexander (El Niño) Daza. Hugo Chávez has said that he wants to

remake Venezuela into “a sea of happiness and of real social justice and

peace.” His pronounced goal was to elevate the poor. In Caracas, the

country’s capital, the results of his fitful campaign are plain to see.

For decades, as one of the world’s most oil-rich nations, Venezuela had a

growing middle class, with an impressively high standard of living.

Hundreds of thousands of immigrants from the rest of Latin America and

from Europe helped give Caracas a reputation as one of the region’s most

attractive and modern cities. That city is barely perceptible today.

After decades of neglect, poverty, corruption, and social upheaval,

Caracas has deteriorated beyond all measure. It has one of the highest

homicide rates in the world; last year, in a city of three million, an

estimated thirty-six hundred people were murdered, or about one every

two hours. The murder rate in Venezuela has tripled since Chávez took

office. Caracas is a failed city, and the Tower of David is perhaps the

ultimate symbol of that failure. The Tower, a ziggurat of mirrored glass

topped by a great vertical shaft, rises forty-five stories above the

city. It is visible from everywhere in Caracas, which is still mostly a

city of modest buildings. The Tower is named after David Brillembourg, a

banker who made a fortune during Venezuela’s oil boom, in the

seventies. In 1990, Brillembourg launched the construction of the

complex, which he hoped would become Venezuela’s answer to Wall Street.

But he died in 1993, while it was still under construction, and shortly

after his death a banking crisis wiped out a third of the country’s

financial institutions. The construction, sixty per cent complete, came

to a halt, and never resumed. Seen from a distance, the Tower gives no

indication that there is anything wrong with it. Closer up, however, the

irregularities in its façade are clearly evident. In places, glass

panels are missing and the gaps have been boarded up; elsewhere

satellite dishes poke out like toadstools. The whole complex is an

unfinished concrete hulk—one in which people are living. Roughly built

brick houses, similar to the ones that cover the hillsides around

Caracas like scabs, have filled vacant spaces between many of the

floors. Only the upper floors are open to the air, like platforms for a

great wedding cake. Guillermo Barrios, the dean of architecture at the

Universidad Central, says: “Every regime has its architectural

imprimatur, its icon, and I have no doubt that the architectural icon of

this regime is the Tower of David. It embodies the urban policy of this

regime, which can be defined by confiscation, expropriation,

governmental incapacity, and the use of violence.” Discusses the

personal history of the Tower’s “boss,” Alexander (El Niño) Daza. Asked

how he had become the Tower’s jefe, or leader, he pursed his lips

and said, “In the beginning, everyone wanted to be the boss. But God

got rid of those he wanted to get rid of and left those he wanted to

leave.” Describes Daza’s religious conversion, and his plans for

improving life in the Tower along socialist lines. Describes how life is

lived inside the Tower: young men with motorbikes operate a mototaxi

service for residents on high floors, driving them from street level to

the tenth floor of the attached parking garage, from which they can

ascend by rudimentary concrete stairwells. Daza has installed a

generator-powered water pump, and the Tower has several bodegas, a hair

salon, and a couple of ad-hoc day-care centers. Writer visits with Daza,

tours the Tower with him, and attends a church service at which Daza

preaches. Describes Chávez’s various programs aimed at helping the poor,

and his encouragement of invasión—the taking-over of abandoned buildings by the poor and homeless. Writer meets various malandros,

or thugs, who exercise power in Caracas’s slums by force. Writer visits

with the leaders of a few slum-based collectives. Describes Venezuela’s

extremely dangerous and overcrowded prisons, where the cultura malandra has flourished. For the writer, it was difficult to tell whether Daza was a malandro

or a genuine advocate for the poor, or both. What seemed clear was that

he was perfectly adapted to life in Hugo Chávez’s Venezuela, able to

gain advantage by every means: working the gaps left by the government,

hustling a capitalist enterprise, and negotiating the criminal

underworld when necessary.

Read more: http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2013/01/28/130128fa_fact_anderson#ixzz2J6jHf8jb

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario